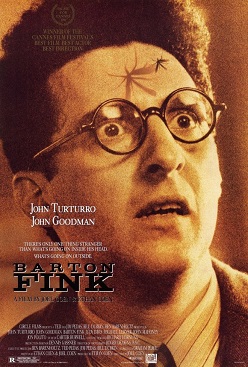

Barton Fink, 1991

Dir: Joel Coen (and Ethan Coen)

June 7, 2009

Netflix Wakefield MA

Writing, in itself, is never an easy thing, especially when you write for someone else. While this is not what Barton Fink is totally about, it is the main dilemma that the title character faces in the film. Barton's (John Turturro) "problem" with writing spirals until it's hard to tell if what is happening is real or not. The Coen Bros. tale of Hollywood script writing finds a man trying to make a difference with his writing, and coming to grips with the choices that people must make while working there and how it affects them.

Barton is a hot young playwright in New York when the film begins, getting lauded by the critics ans his fans alike for his portrayal of the "common man." One of his close associates convinces him to take a contract job at a film studio, despite his obvious doubts and his desire to write something better. His time in LA is lonely and isolated, as he tries to write a "B" movie wrestling flick that the studio wants but is suffering from a case of writer's block. From there, Barton's hold on reality seems to slip as things, literally, fall apart around him.

The hotel where Barton stays is the main focus of his isolation. He stays in a crappy hotel that has clearly seen better days, and never sees any of the other tenants, save one. Charlie Meadows (John Goodman) lives next to Barton and occasionally comes over after their first meeting where Charlie demands to know if it was Barton that had called to complain that he had been making too much noise (Charlie had been crying). Their conversations run from Charlie's work as an insurance salesman to the details on how to wrestle. The whole relationship is really buddy-buddy, but also displays Barton's main problem. While he is intent on creating this "new" theater for the "common man" about real people, he refuses to listen to Charlie, who is the definition of a common man, "who has stories to tell, believe you me." Barton's thoughts on "the life of the mind," that which he believes he lives and separates him from people like Charlie, comes back to haunt him as Charlie's character reveals itself to be not quite what Barton had assumed.

In seeking out help to write the film, Barton bumps into one of his literary heroes, W.P. Mayhew (John Mahoney) and picks his brain for advice. The man turns out to be a drunk and completely spiteful of the whole Hollywood scene (allusions to William Faulkner), who may not have written all of his work anyways. He has a beautiful secretary, who is also his lover, who has ghost written many of Mayhew's script's while he has been too drunk to write. In a nervous moment, Barton calls this secretary to help him because his is coming up to a deadline. She comes over, and after confessing that he is having serious problem coming up a script, she tells him she will help him "relax." They have sex. When Barton wakes up, however, she is dead; butchered in his bed. Charlie helps him get rid of the body, but he soon has to leave for work, and cops (who are pretty hilarious) start sniffing around. Much to Barton's surprise, they are looking for Charlie, who is actually the serial killer "Madman Mundt" who decapitates his victims and keeps the heads. Before he left, Charlie had left a head sized package with Barton, and when they first said the things about decapitation, I was like, "Oh Shiyyyyyyyyyyyyt!" But it wasn't the half of it.

Barton's new experiences force out of him a script that he thinks is his best work yet. After coming back from a night of dancing, the cops are at his place, but Charlie comes back and the entire hotel erupts in flames. Running down the hallway blasting the cops with a shotgun, Charlie screams "LOOK UPON ME! I'LL SHOW YOU THE LIFE OF THE MIND!" With the fire raging all around and John Goodman barreling down the hallway, it is one of the most mesmerizing scenes I've ever watched. Soon after Barton and Charlie chat, and Charlie finally gets across that the pain and yearning felt by Barton, that which he tries to get across in his writing, is also felt by the common man, especially himself. The incendiary hotel is Charlie erupting, his pain and anger raging forth, and a fiery representation that his life may be in fact more complex and emotional that Barton's. His killings, even the one that he forced upon Barton (Audrey, the secretary), he explains are in fact a release: "Most guys I just feel sorry for. Yeah. It tears me up inside, to think about what they're going through. How trapped they are. I understand it. I feel for 'em. So I try to help them out." Maybe with this new understanding of the empathy needed to relate to the common man, Barton can create the thing he so desires.

But of course his script is dismissed by Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), the movie studio head who's been singing Barton's praises the whole time, as a "fruity film about suffering." Lipnick is a composite of all the old Hollywood heads of ol', the blustering philistines who demand great art but know nothing about it and peddle formulaic entertainment for economic gain, and is the main representation of Barton's struggle of writing good material versus compromising for "the pictures."

I think I'll finish (though there is still plenty to talk about) with the picture in Barton's room and the final scene. Wandering onto the beach after being rebuffed by Lipnick, a beautiful girl comes out on the beach and sits down if front of him. The last shot mimics the picture where a girl sits on a beach looking out at the ocean. I've thought a lot about this, trying to put any kind of meaning behind it, and it seems to suggest the relationship between art and reality; what is in our heads and what we really see, and how art can mimic reality. This in turn puts doubts on what really happened in the film. Did it happen at all? Was this just a story made up in Barton's head that allowed him to mature as a writer? An extremely complex internal epiphany? In one scene where Barton is having trouble writing, he opens the Bible in his desk directly to Daniel, the passage where he is trying to interpret King Nebuchadnezzar's dreams. This seems to allude to some sort of unreal element about what is going on, and it only increases as the film builds to it's climax. The shots of slowly going down hallways and of going into things, as if you are going into someone's mind, might suggest this, and the entire nature of the hotel almost feels not real, so there is definitely a chance that the hotel induced some sort of frayed reality. The enigmatic last lines of the film also suggest something of this nature: Barton tells the girl that she is beautiful, and then asks, "Are you in pictures?" She blushed and replies, "Don't be silly." It is impossible to be certain because the film is purposefully enigmatic in this way, but they certainly want you to ponder certain things. All I know is that there are a lot of things to think about after watching this film, and it is probably the best Coen Bros. film I've seen.

1 comment:

Best Coen Brothers? What about "Ladykillers," or Intolerable Cruelty?" Get tha' net.

Post a Comment